by UCIRA Co-Director Kim Yasuda

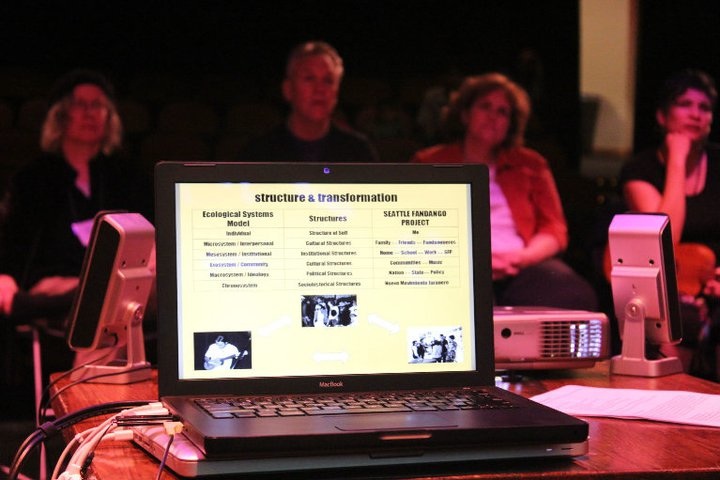

(Photo: UCIRA Co-Director Kim Yasuda presenting “Proximity Research” at OnStream 2011 for Foundations in Art – Theory + Education (FATE) and Mid America College Art Association (MCAA) St. Louis, Missouri, 2011.)

Spending this year off-site brought the expected shift in perspective that sabbaticals tend to do. At a distance, I had the opportunity to reflect upon my proximity work at UCSB and the previous five years of arts research across our system within a national field of emerging forms and big ideas . Reviewing the field notes, I see value in documenting those projects that have evolved through place-based strategies on a number of our UC campuses. Taken in as a series of linked local demonstrations, a strong case could be made for valuing the work we do in and around the intimate spaces and vast holdings of our system. UCIRA planning and implementation funding for projects and gatherings under the category, Social Ecologies: Art + California has initiated support for work about the system itself.

As I write this, Berkeley professor, Catherine Cole has begun her investigation into a fifty-year old archive of the University of California, consisting of some 6000 photographs by Ansel Adams as a commission by then UC president, Clark Kerr. The collection documents the campuses of the early 1960’s as part of what would be the premiere university system whose intellectual capital would make good on the public investment in California’s future. As Cole describes it, this ‘ethnographic’ study of the archive is shaping the topic for her next book (see Catherine Cole’s SOTA interview). Based on her recent paper, “Trading Futures: Prospects for California‘s University“, Cole is planning the re-institution of the all-UC faculty conferences as a series of system-wide planning workshops or ‘charrettes’ to harness the intellectual and creative leadership of our scholars and artists in a revisioning of UC’s future.

At the same time, UCI History and Media Studies Professor Catherine Liu with graduate student, Cole Ackers began an urban history study, panel and exhibition, “Learning from Irvine” about the city of Irvine and UC’s pivotal role in the planned community. In 1959, the University of California asked The Irvine Company for 1,000 acres for a new campus. The University’s consulting architect, William Pereira, and Irvine Company planners drew up master plans for a city of 50,000 people surrounding the university. The area would include industrial zones, residential and recreational areas, commercial centers and greenbelts. Both Cole and Liu’s research calls attention to the embedded presence of UC in the unfolding of California’s post-war development history as it continues to play out in the state’s transitional present.

(Photo: Raymond L. Watson (pictured on the right), former president of The Irvine Company, 1964. Watson began his career as CEO and President of The Irvine Company in September 1960. The archive is housed at UCI as part of its Special Collections. The Raymond L. Watson Papers (MS-R120) pertain to the planning history for UCI and the City of Irvine.)

In my travels to other institutions across the country, I also recognize this turn toward the intimate and proximate. These overlooked spaces, oftentimes within or just outside of the borders of the university, provide the sustained residency time for research to take hold and embed itself fully. Further, proximity opens up the prospect for a different set of relationships to be forged between scholarship and community. Each setting presents a different set of research questions, whether within the space of one neighborhood or across an entire state.

The challenge now appears to be how and to what end should these distinct localities become linked or mobilize toward some collective end? Attending the circuit of national conferences this year, I heard many of the same concerns: the need to organize translocal communities and communications platforms between individuals and institutions to address larger challenges faced by all communities; to collectively develop a national advocacy campaign for the arts to draw the value of its research back into the center of national campaigns on education, institutional reform, cultural development and economic revitalization. Finally, from all sectors, I listened to a call for the role of assessment as the means to track, quantify and disseminate the value of the work we do — from classroom grading and teaching evaluations to audience participation and professional placement of our arts graduates. “What counts” takes hold as technology enables us and the public demands more tangible forms of evidence beyond the qualitative and anecdotal data that we in the arts are accustomed to relying upon in justification of the work that we do.

(Photo: Imagining America’s 11th Annual Conference, Convergence Zones: Public Cultures and Translocal Practices, included site visits to University of Washington’s urban farm and other non-profits in the greater Seattle area, 2010)

One Conference After Another? Rethinking + Linking Gatherings

Since UCIRA co-hosted its 4th annual State of the Arts conference with UCSD last Fall, we have begun to rethink the future of academic conferencing and new ways to link artists across our own system through more effective forms and alternative models for knowledge transfer and exchange (see UCIRA Associate Director Holly Unruh’s reflections on SOTA). Circulating national convenings this year, I noticed the large number of discussions on arts research taking place outside of more traditional disciplinary forums such as College Art Association (CAA). Broadly defined contexts for shared thinking lend a different tone and pulse, situating the arts within more expansive frames of study, such as public scholarship, social practice, pedagogy as well as focus on more general topics such as undergraduate and graduate research and the future of higher education. The setting draws a cross-sector of scholars, practitioners, educators, administrators and community participants around a table, generating a distinctly different context for discussions to take place outside the focus of any one discipline.

(Photo: Imagining America Convergence Zones: Public Cultures and Translocal Practices: Site visits to non-profits in the greater Seattle area. UCIRA board member and UC Davis Director of Art for Regional Change, Jesikah Ross, leads a group of conference participants off-site to the community media lab, 911 Media Arts.)

Imagining America’s 11th annual conference, hosted by the University of Washington, brought together more 350 attendees for 3 days in Seattle. Imagining America (IA), now in its 12th year, is a consortium of more than eighty-five colleges and universities “committed to building democratic culture by fostering public scholarship and practice in the arts, humanities, and design.”(1)

Developing the conference around a thematic frame, Convergence Zones: Public Cultures and Translocal Practices, organizers Bruce Burgett and Miriam Bartha, directors of the Simpson Center for Public Humanities shifted the academic discourse off-site to take place within the greater Seattle area through their co-planning and hosting with community organizations. While two days were dedicated to a more typical schedule of keynotes, panels and presentations, a day was offered for off-site visits to significant cultural organizations that actively engaged in community knowledge production, challenging the usual borders between the academy and community.

(Photo: Imagining America Seattle Conference site visit at the Seattle Fandango Project, a non-profit community arts organization bringing ecological systems models through dance to underserved communities.)

Further, experiments in conference structures were expanded through a series of pre-conference research groups, made up of individuals across the IA network. Topic-based discussions were developed several months ahead, culminating in tightly focused seminars that worked throughout the three-day conference. Included were “community scholars”, or non-university affiliates who brought their outside academic expertise to knowledge making practices (See SOTA interview with Gilda Haas about a similar program at UCLA). As another means to link the activity of a conference to a year-round think-tank, IA launched its series of research “collaboratories” that also worked at the Seattle conference, creating research opportunities for IA membership to be co-principal investigators on topics critical to IA’s mission, such as “community knowledge”, “assessment”, “tenure”, “undergraduate and graduate liberal arts education”. The findings of these research groups will be presented at IA’s annual conference, in Minneapolis The Spaces between Us, hosted by Macalester College and the University of Minnesota .

In a report from the mid-west, academic-affiliates from across the US, primarily arts practitioners who teach college level fundamental/foundation courses, participated in OnStream 2011 in St. Louis this past winter. The conference was co-organized by the national consortium, FATE: Foundations in Art – Theory + Education and MCAA, the mid-America College Art Association. Since the 1982, FATE, whose membership represents independent colleges of art and design, university art departments and community colleges throughout the U.S. has promoted excellence and innovation in arts foundations. MCAA, formed in 1930, has provided “a forum for the artist/teachers of America to discuss and debate the issues of their profession, to share ideas and information of mutual benefit.” With particular focus on arts education at the undergraduate level, attendees came to address and exchange ideas over the current state of core training in the arts in a climate of diminished resources. How are visual art skills imparted to more students with less or no exposure to the formal arts? What constitutes training of the artist in the 21st century? How should the academy respond to a new generation of students? As expected, current budget reductions have placed additional pressure on the adjunct sector (usually part-timers and graduates). Nonetheless, precarity, not tenure, appeared to fuel a high degree of risk and innovation in the classrooms amongst this group.

(Photo: Opening reception of Game Show, NY, Columbia Teacher’s College, NY, 2011)

The recent Columbia University Teachers College conference, (Creativity, Play and the Imagination) brought several hundred educators, administrators, artists and teachers to New York to discuss the role of creativity from early childhood to higher education. The conference, organized by PhD candidates and visual artists, Nick Sousanis and Suzanne Choo, showed evidence that a significant numbers of our MFA-trained artists are now finding their way into educational systems both to teach and to innovate through their creative practice within the alternative spaces of the classroom. Further, within the conference structure, Sousanis and Choo co-curated an exhibition, Game Show, New York at the Macy Art Gallery. Funded by a research innovation grant from Microsoft, 27 artist-designed games for learning were showcased during the month of the conference.

Younger artists are recognizing opportunities for engagement within broader institutional and social realms and are willing to embed themselves within situations that call upon their creativity to problem-solve, rather than to simply showcase and promote their work. In my view, this is a positive indicator of systems in transition that are changing both the academic and professional pathways for artists. This particular conference included K-12 education, which has become increasingly relevant to higher ed arts training as a national teaching-to-the-test climate drives primary and secondary school educators away from innovation in order to meet state standards. As I point out above, this has had direct impact in our recuperation work at the university level, guiding students to shed unimaginative learning models from their past experience. It seems to me that foundation arts curricula must also include a retraining of our students to identify themselves as independent thinkers and further, that their responsibility as artists is not only to make and reflect, but to innovate, take risks, fail and take charge of their future.

Through UCIRA, we are working with UC arts faculty to pilot a series of freshman seminars that begin to bridge this gap in a student’s initiation to the university, making sure that arts are not extra-curricular, but integrated at the front line of the college experience.

(Photo: Luis Rico-Gutierrez, Dean of Design Administration and Professor of Architecture at Iowa state University, engages in the work-play group on “research” at the University of Michigan ArtsEngine on “Arts Making, The Arts, and The Research University”, May 4-6, 2011.)

This past May, University of Michigan’s ArtsEngine gathering on “Art-Making, The Arts, and The Research University” drew national campus leadership and arts agencies, including NEA, NSF, Mellon and Dana Foundations for the 3-day meeting. Arts and Science deans, provosts and high-level academics attended from many top-tier research institutions across the country to engage in collective work sessions that began to address the necessary infrastructures to renew institutional vision and build campus innovation. Mixed working groups were assembled across institutional and disciplinary lines to analyze and propose new strategies for integration of the arts under the rubrics of “research”, “curricular”, “co-curricular”, “case-making”, “funding” and “national networks.” Vision and strategic planning statements were culled and circulated from each group to become the foundation for a white paper to guide movements toward institutional change.

In her keynote for the Michigan conference, Syracuse University President Nancy Cantor, describes her own “bottom up + top down” leadership strategies for shifting campus behavior by providing innovative reward structures for students and faculty across curricular and research sectors at the ground level of a few engaged individuals. Her office has encouraged project-based courses to form organically around local conditions and salient topics that bring cross-sectoral approaches to problem-solving outside of any one discipline and included the arts, urban planning, business administration, science and public health. These publicly engaged projects foster unprecedented partnerships to emerge between students, faculty, community and government agencies, encouraging a re-patterning in the form and spaces of academic research. In Cantor’s view, the incentives for new ideas to develop at the ground level can transform the intellectual culture of the research university in ways that could not be administered in the usual, bureaucratic ways. (for Cantor’s keynote see video and her slides).

The Michigan conference placed particular emphasis on the crossover potential for Art/Science paradigms and partnerships, capturing the attention of high-level administrators in science and engineering to consider the role of arts research. Pamela Jennings, artist and program director at NSF, has instigated a tri-institutional partnership between Rhode Island School of Design, Rensselaer Institute and Arizona State University to develop “STEM to STEAM” case studies that embed and harness the agency of artists within art/science research clusters. In her presentation, Jenning’s assessment of the current state of program development finds that while there are numerous efforts operating independent of one another across many institutions, critical bridging and mobilization needs to take place now at the policy level to develop an effective platform that positions the role of arts and artists squarely within research clusters as an integral component to new knowledge production. Further, she saw the need for new assessment strategies that offer self-study opportunities for institutions, while generating the kinds of data that speak to foundations and policy makers.

Also at Michigan, a current model of assessment research on the arts was presented by George Kuh, director of Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. Kuh heads the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP), a five-year study that documents alumni student engagement in the arts. 2008-2010 field tests drew from 250 institutions from 42 states with more than 13,581 alumni respondents. The pre-study reveals key findings specific to the arts within a national professional landscape and has drawn national media attention to the significant role of arts research within a public platform.Following this pilot period, SNAAP will fully launch this year to be the most comprehensive national study on the education of artists to date.

Rethinking What Counts: Self-determined Self-assessment

The language of ‘assessment’ is often received with a degree of suspicion by those in our field who already recognize and acknowledge the inherent value of the arts and fear that the demand for hard data usurps art’s autonomy to operate independent of a public agenda. However, to study ourselves and ask critical questions of our artists could provide a significant dimension of understanding to the work we do as scholars and artists whose professional field training comes by way of the academy. Further, we have a stake in what questions are asked, how they are framed and in so doing, we claim a degree of authorship and agency over the data that is drawn, sometimes erroneously collected on our behalf by national surveys, such as those conducted by US News and World Reports.

Recognizing the opportunity for a data profile drawn specifically from and for UC arts, UCIRA has worked this past month to partner with all eight UC arts deans at Davis, Santa Barbara, Berkeley, Irvine, Los Angeles, Santa Cruz and Riverside for our full system participation in the forthcoming 2011 SNAAP survey. UCIRA also secured a $50,000 Opportunity Funding from the research division of UCOP to subsidize the inclusion of all arts campuses in the study. The data collected specific to UC arts alumni will serve as a valuable resource tool in assessing our work across the state. To further benefit from this self-study, UCIRA intends to pursue NEA funding to conduct analysis on the data collected from the 2011 SNAAP findings.

While UC arts links its work to these national networking efforts, fewer California research institutions appear to be participating in these forums as the state’s economic turn takes hold on matters closer to home. To what degree do our UC artists join forces in national policy initiatives such as those mentioned above, given the challenges before us? How might one local/regional/national condition link to/inform/serve the other?

UC has had little choice but to hunker down and address its regional place within the service of the state. Yet, we need to find ways to influence national policy to bring art/artists to the center of our nation’s cultural agenda and its reimagining of the future. Especially in forums that address the role of arts in academic research and public education, practitioners in the arts are less often brought in, nor actively engaged at a policy level. However, in my survey of programs and conferences across the country, I am encouraged to see a growing number of both younger and well-recognized artists willing to expand their professional careers and alternative practices toward their teaching, administrative and organizing leadership within and outside the ranks of the academy.

While this re-visioning work may not be squarely centered within the conventions of a creative practice as we know it, the organizing and mobilization toward this change-agenda has become an integral part of a movement that many colleagues across the country consider to be the emergent field of scholarship. In a recent design conference keynote at Hunter College, Erasing Boundaries, David Scobey, Vice Provost of the Parsons-New School states, “Publicly-engaged research is the intellectual project of the 21st century”.

1) Imagining America—Engaged Scholarship for the Arts, Humanities, and Design, Robin Goettel and Jamie Haft, Imagining America, Syracuse University, 2010.

First launched at a 1999 at a White House Conference, Imagining America was initiated by the White House Millennium Council, the University of Michigan, and the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation. The conference brought together government officials, scholars, artists, university presidents, foundation executives, and nonprofit leaders to describe, debate, and look for new opportunities for civic engagement in higher education. Participants reached a consensus about what was needed for public scholarship and practice to flourish: a national network, legitimization, and financial support.

After the conference, twenty-one participating college and university presidents agreed to build a national network with the formation of the Presidents Council. This Council became the basis for what would become Imagining America’s consortium of colleges and universities. (To this day, a college or university president or chancellor must sign the Imagining America membership agreement.)